Mujitsu and Tairaku's Shakuhachi BBQ

World Shakuhachi Discussion / Go to Live Shakuhachi Chat

You are not logged in.

Tube of delight!

#26 2011-02-13 22:00:32

- Karmajampa

- Member

- From: Aotearoa (NZ)

- Registered: 2006-02-12

- Posts: 574

- Website

Re: Planar Tone Holes

Yes, I agree that fine tuning errors show up more in the higher octave than the lower. A Shakuhachi making friend was always playing in the Otsu octave, I pointed this out to him on several of his flutes by playing the Kan octave and Chi and Ri Kan were all flat, Oops !

K.

Kia Kaha !

Offline

#27 2011-02-13 23:23:24

- Toby

- Shakuhachi Scientist

- From: out somewhere circling the sun

- Registered: 2008-03-15

- Posts: 405

Re: Planar Tone Holes

Grosser tuning errors between registers are due to overall errors in the bore profile, which either stretch or narrow the modes. They usually occur in the upper bore.

Offline

#28 2011-02-14 00:36:26

- Alan Adler

- Member

- From: Los Altos, California

- Registered: 2009-02-15

- Posts: 78

Re: Planar Tone Holes

I'd be interested in hearing others opinions about tuning errors.

It seems to me that they aren't of much concern with shakuhachi. I would think that tuning errors are most obvious when attempting to harmonize with other players. But even then there are errors in harmony due to the fact that most scales are tempered - at the price of harmony.

And most of the shakuhachi performances that I've heard were solo - where errors in tuning are less noticeable.

And finally, pitch is greatly affected by embouchure with a shakuhachi - even more than it is with a transverse flute.

So are we concerned about tuning errors? Can't the performer easily adjust the pitch with his embouchure? Riley Lee demonstrated to me that he could bend the pitch up or down about three semitones. Although at that extreme the timbre suffered substantially.

Looking forward to comments.

Alan

Last edited by Alan Adler (2011-02-14 00:51:51)

Offline

#29 2011-02-14 02:01:00

- Karmajampa

- Member

- From: Aotearoa (NZ)

- Registered: 2006-02-12

- Posts: 574

- Website

Re: Planar Tone Holes

"so are we concerned with pitch ?" - are you serious ?

Yes, a Shakuhachi can be tuned to a particular key, not so easy if bamboo is the material, it is often cut to do this. I don't cut and re-join, I like to have a node at each end, seven if that fits, sometimes more, sometimes less. but each of my flutes is tuned within itself, usually by ear as they are not designed to fit particular keys, though some do fit and I can adjust length or bell to help it fit.

You comment on Riley taking a hole through three semi-tones, not a problem, but you ideally want each hole to be 'on pitch' for example if you want to take a hole down three semi-tones but it is already flat by a semi-tone then what are you going to get ?

If you want to do a quick run up the scale, you don't really want to have to bend one particular hole each time.

There are incidences where a flute has such lovely tone but one hole is off-pitch but altering it may deteriorate the tone so it is compromised.

You can blow harder to sharpen a note but that will also alter volume and tone so why would you not prefer that hole to be more correctly tuned ?

Unless one is somewhat tone deaf, .......

K.

Kia Kaha !

Offline

#30 2011-02-14 02:06:13

- Tairaku 太楽

- Administrator/Performer

- From: Tasmania

- Registered: 2005-10-07

- Posts: 3226

- Website

Re: Planar Tone Holes

Most of the flutes I play are "sharp" on chi, so I'm used to making that adjustment every time I get to that note. I don't think it's possible to really make a flute that plays in tune, because it's the player who makes it in tune as much as the instrument. You can make a flute which is fairly close to being in tune but the difference lies with the player.

'Progress means simplifying, not complicating' : Bruno Munari

http://www.myspace.com/tairakubrianritchie

Offline

#31 2011-02-14 19:36:02

- Alan Adler

- Member

- From: Los Altos, California

- Registered: 2009-02-15

- Posts: 78

Re: Planar Tone Holes

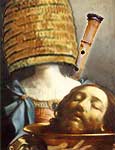

I played scales (an octave plus two notes into the second register) into the Syaku tuner on the flute pictured here and on an aluminum flute with the same ID. All notes were within about 10 cents with no special effort to adjust by embouchure.

I don't know if that's considered good or bad, but it sounded quite acceptable to me.

Best,

Alan

Last edited by Alan Adler (2011-02-14 19:46:55)

Offline

#32 2011-02-14 20:36:04

- Karmajampa

- Member

- From: Aotearoa (NZ)

- Registered: 2006-02-12

- Posts: 574

- Website

Re: Planar Tone Holes

10 cents is barely perceptible, good tuning.

K.

Kia Kaha !

Offline

#33 2011-02-15 22:24:52

- Toby

- Shakuhachi Scientist

- From: out somewhere circling the sun

- Registered: 2008-03-15

- Posts: 405

Re: Planar Tone Holes

Alan Adler wrote:

I'd be interested in hearing others opinions about tuning errors.

It seems to me that they aren't of much concern with shakuhachi. I would think that tuning errors are most obvious when attempting to harmonize with other players. But even then there are errors in harmony due to the fact that most scales are tempered - at the price of harmony.

And most of the shakuhachi performances that I've heard were solo - where errors in tuning are less noticeable.

And finally, pitch is greatly affected by embouchure with a shakuhachi - even more than it is with a transverse flute.

So are we concerned about tuning errors? Can't the performer easily adjust the pitch with his embouchure? Riley Lee demonstrated to me that he could bend the pitch up or down about three semitones. Although at that extreme the timbre suffered substantially.

Looking forward to comments.

Alan

In the "old days" the shakuhachi was a solo instrument and therefore tuning errors were not so much a problem. But when it became more part of ensemble playing, and specifically when it started to be used in diatonic "Western" music, tuning became critical. You probably know that the specs for different sized flutes was altered from strictly length-based (according to units of shaku and sun) to approximations that played the correct diatonic frequencies. Meijiro still sells sets of tuning sticks (indicating length and hole positions) for both conventions.

The best absolute measure of tuning are impedance plots: a sweep of frequencies is played and the tube is analyzed to see at which frequency the acoustic flow is greatest. This needs to be done for each tube length (fingering). This shows the "native" frequencies at which the tube would be most likely to resonate.

Of course the end correction at the top, depending on hole shading with the mouth, will change those frequencies when the flute is blown. But the point of the game is to have the flute sound the correct frequencies when the mouth is in the best position to achieve the note desired. This makes matters a bit tricky.

Take, for example, a normal Boehm flute. We hope that when we overblow to the second octave, the notes will be in exact harmonic relationship. But to overblow the second octave, we need to actually change the mouth position somewhat as well as blowing harder in order to achieve the best sound quality and control dynamics. The player blows somewhat harder, but also shortens the distance from lips to blowing edge somewhat. This is an interesting little dance.

Overblowing to the octave involves changing the timing of the air jet to support the higher frequency. There are two ways of changing the timing, adjust the air speed or adjust the length, or both. But air speed is a second-order function of blowing pressure--to double the speed you have to blow four times as hard. This not only makes the octave loud, it changes the tonal quality. But jet timing is directly proportional to jet length, so an experienced flautist blows somewhat harder but also moves the lips slightly forward to shorten the jet. This allows him to play the higher octave with better tone quality and with controlled dynamics.

But moving the lips forward increases end correction and thus flattens the note. Therefore, Boehm flutes have a build in "de-adjustment" to make the upper mode sharp in relation to the lower mode, so that when the player moves his lips forward, increasing end correction, that automatically brings the octaves back into line. This is the function of the "parabolic head joint", where there is a contraction of diameter near the embouchure hole. The contraction actually widens the modes, to compensate for the flattening of the second mode when the player adjusts his embouchure to play the octave.

Old-style flutes and shakuhachi use a different, but similar trick. In both, the upper part is cylindrical, but the lower part is reverse-conical (contracting towards the lower end). This also has the effect of widening the modes, and thus brings the octaves back into line.

So the name of the game is to have the notes in tune for the "ideal" embouchure for any given note, ideal meaning the mouth position in which the tone quality is best (which is different for the different registers). Also, neighboring notes should be in tune without the need for embouchure adjustments.

Neighboring notes can be tuned according to hole size and placement, and the octave relationships generally can be tuned by altering the upper bore, whereas individual variation between octaves can be adjusted using Rayleigh perturbation theory.

Of course most of this is unimportant if you are only playing the first octave.

Offline

#34 2011-02-20 21:52:02

- Toby

- Shakuhachi Scientist

- From: out somewhere circling the sun

- Registered: 2008-03-15

- Posts: 405

Re: Planar Tone Holes

Hey! Here's something interesting concerning vent holes at the end of a flute.

Here in Beijing I have a dizi flute. It is side-blown like a concert flute, but like Alan's flute it is extended, with four holes near the end for the last note. Just for fun I tried covering those four holes with one hand while playing with the top hand. To my surprise, I found a major difference in both the response and intonation of the note played with all three right hand fingers down (in the second octave).

This note still leaves three finger holes uncovered below it before the holes at the end, and I would have thought that those three finger holes would have vented the flute sufficiently that the end holes were of no consequence, but this was clearly not the case. And uncovering just one of the four end holes was enough to make the sound and response of that note almost identical to that of playing the note will all four holes uncovered.

The dizi has a finger hole to bore size ratio which is larger than the shakuhachi. To me this indicates that hole sizes (and or chimney heights) in a shakuhachi can be of major importance to the sound and response of certain notes. So it is not enough to simply measure or adjust the "pressure points", one has to take into account how the open tone hole lattice affects things, especially in the second octave (kan). Very interesting...

Offline

#35 2011-02-20 22:59:18

- Moran from Planet X

- Member

- From: Here to There

- Registered: 2005-10-11

- Posts: 1524

- Website

Re: Planar Tone Holes

Karmajampa wrote:

10 cents is barely perceptible, good tuning.

K.

As long as it's cents and not hertz. ![]()

"I have come here to chew bubblegum and kick ass...and I am all out of bubblegum." —Rowdy Piper, They Live!

Offline

#36 2011-02-21 04:22:39

- Toby

- Shakuhachi Scientist

- From: out somewhere circling the sun

- Registered: 2008-03-15

- Posts: 405

Re: Planar Tone Holes

Moran from Planet X wrote:

Karmajampa wrote:

10 cents is barely perceptible, good tuning.

K.As long as it's cents and not hertz.

That hurts, but it makes sense...

Offline