Mujitsu and Tairaku's Shakuhachi BBQ

World Shakuhachi Discussion / Go to Live Shakuhachi Chat

You are not logged in.

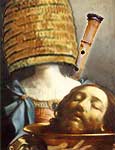

Tube of delight!

#1 2014-01-26 16:19:28

- Tairaku 太楽

- Administrator/Performer

- From: Tasmania

- Registered: 2005-10-07

- Posts: 3226

- Website

Primitive Shakuhachi in a Post-Modern World-3 CDs

Primitive Shakuhachi in a Post-Modern World

Vault-David Kotlowy (shakuhachi) and Ross Bolleter (ruined pianos).

From the Devil's Mountain-Mike McInerney (shakuhachi)

Kamakura Jūniso- Sabu Orimo (jinashi shakuhachi)

Shakuhachi, of course, originated in the realm of Japanese traditional music. We are currently in a modern music world with no boundaries. The last hundred or so years have seen shakuhachi players experimenting with taking shakuhachi out of the traditional context of Japanese music and interactions with other Japanese instruments such as shamisen, koto and biwa. Sometimes this simply involves plunking the shakuhachi down in the midst of a different musical style such as Western art music or jazz and showcasing it as a visitor. I have chosen to review these three albums together because they attempt other solutions to the problem.

From the Devils Mountain consists of one piece called Listening for Lost Voices. It is recorded at an abandoned Cold War listening station of Teufelsberg Deutschland. It appears to be a huge reverberant silo with a massive decay time. The shakuhachi content consists of amorphous blobs of glissandi, blurting, muraiki, trills and the occasional stab at pentatonic melody. In a highly original move, this is accompanied by a backdrop of intermittent ethereal Morse Code signal chattering and droning in a relaxed fashion. There are also chance percussion episodes, probably the performer's fidgeting. Due to the strange acoustics of the space these are amplified abnormally. We could say it's a sound sculpture formed as much by the experience of playing in that particular space as by the intention of the performer himself.

Vault by Kotlowy and Bolleter continues the theme of harnessing unintentional sounds in the service of spontaneous composition. Ross Bolleter makes the rounds of Australian festivals and arts events banging away on a variety of ruined pianos scavenged from barns, porches, beaches, garages, dumps and other undignified resting grounds. This schtick could get old fast if not for the fact that the musical results are often thrilling. If you're like me and bored with the musical hegemony of piano and its predictable tuning system you'll enjoy the racket emanating from the rubble. It ranges from deep gong like sustain to stuck typewriter to gamelan-like effects. The liner notes state that Kotlowy studied shakuhachi for one year with Kakizakai Kaoru and Kodama. Results are raw improvisation and some honkyoku licks mostly on jinashi Kodama flutes. Sounds somewhat similar to early efforts by Sabu Orimo. Some of the pieces appear to have been organised beforehand, due to unison playing. But when you have unison between a trashed out piano and slipping and sliding jinashi it's still moderately random.

Speaking of Sabu Orimo, here is the latest and greatest from the enfant terrible of noise shakuhachi. Kamakura Jūniso is a self-concious attempt by Sabu to create a positive sound world of idyllic and utopian splendour. This is in contrast with his previous efforts in free improvisation which sometimes sounded like inchoate cries for help. I have always considered Sabu to be a process artist and this time he has moved to the city park of Jūniso in Kamakura and absorbed the nature and peaceful surroundings. Much is made of shakuhachi as meditation music, but usually it's imitation music. Here one gets the sense that Sabu has truly spent a lot of time in meditation on his surroundings and on this next step in his personal musical journey. In the liner notes and in a message he sent me, Sabu says the music reflects the birdsong, mountain and ocean of this environment. In fact one can hear the birds chirping along with Sabu's jinashi on some of the tracks. Considering that some scholars hypothesise that human music making started with imitating birds, and Sabu's previous claim to be a stone age musician, there's some consistency with his previous work. This is the most conventionally listenable of Sabu's recordings. They are mostly improvisations recorded in one take. The building blocks of Sabu's improvisations are available to most good shakuhachi players. What makes Sabu different than most is his concentration ability and the commitment he brings to the improv. Track number 4, English title Grand Bleu, is a fascinating exploration of the one note and harmonics of a very long, probably 4.0, hole-less jinashi shakuhachi.

I have reviewed these CD's together for the coincidence that they came into my view at the same time, but also because I think these artists are addressing their place in post-traditional shakuhachi music in interesting conceptual ways. None of them are virtuosi. In fact Sabu Orimo, who has always been considered a renegade, sounds almost like an elder statesmen in this company, and it's his music that has the clearest connection with the honkyoku tradition. All of these artists could benefit from more technique and traditional knowledge, which would give them larger vocabularies from which to draw their improvisations. With these recordings they have all offered novel approaches to contemporary shakuhachi improvisation and unique collaborations with sounds normally considered non-musical in the form of Morse Code, broken pianos, and nature sounds respectively.

'Progress means simplifying, not complicating' : Bruno Munari

http://www.myspace.com/tairakubrianritchie

Offline

#2 2014-01-26 18:31:11

- Moran from Planet X

- Member

- From: Here to There

- Registered: 2005-10-11

- Posts: 1524

- Website

Re: Primitive Shakuhachi in a Post-Modern World-3 CDs

fouled piano, norway by aaponivi, on Flickr

"I have come here to chew bubblegum and kick ass...and I am all out of bubblegum." —Rowdy Piper, They Live!

Offline